We'll look at how you can transform 2D and 3D space with a Linear Transformation.

Prerequisites

You'll need to know about Linear Transformations.

Applications

Beyond the scope of A-Level Further Maths, Linear Transformations are useful in computer graphics and video games. For example, we might want turn a camera to follow the player. When displaying movement in real-time is crucial, we may need to consider carefully how to minimise the amount of calculation required.

We can also think about extending geometric ideas into higher dimensions. By thinking abstractly about how to extend from 2x2 matrices and linear transformations in 2D, to 3x3 matrices and linear transformations in 3D, we can start to think about what might be possible in 4D space - going from square to cube to tesseract.

General Strategy: Key Points

If you have a transformation matrix , then we can transform the points (1,0) and (0,1):

- , and,

- .

In other words, we see where the point (1,0) transforms to by looking at the first column of the matrix.

We find the image of (0,1) by looking at the second column.

In fact, moving just these two points determines everything we need to know about the transformation (since we can also reconstruct the whole matrix). By looking just at what happens to two points, it's got to be possible to tell what type of transformation we have.

A similar strategy to understand a transformation will also work in 3D, by looking at how (1,0,0), (0,1,0) and (0,0,1) transform. Converting these into the unit vectors:

, , and ,

We can see how they are transformed by looking at the first, second and third column of the transformation matrix.

Specific Types of Transformation

Identity Transformation

Represented by the identity matrix in 2D, and in 3D.

Multiplying a matrix by has no effect - the matrix is equivalent to the number 1 in this sense: 1 is the so-called "multiplicative identity". In some contexts, the identity matrix can be represented by just .

Therefore, this transformation also has no effect. All points stay where they are - all points are invariant.

Recognising the Identity by moving key points

You should definitely be able to recognise an Identity Matrix by looking at it. But, we can also examine what happens to key points.

Looking at how the points (1,0) and (0,1) move:

They are both invariant. This is enough to define the transformation - we can infer that every point will be invariant.

Reflections

Reflections in 2D are of the form

This gives a reflection in the line . In other words, a reflection in the line making an angle of with the positive x-axis.

Note that the determinant, . The negative sign shows that the orientation of any shape will be reversed (flipped) by a reflection. And the area of the shape will be multiplied by |-1| = 1. You could say: the area of any shape will be invariant under reflection.

Note that since the origin is always invariant, the line of reflection must include the origin. In 3D, the plane of reflection must include the origin.

It's useful to be able to recognise reflection matrices from numerical values. They will look something like: .

Recognising simple reflections by moving key points

Suppose we have the transformation matrix A = . We can see how to transform the points (1,0,0), (0,1,0) and (0,0,1), by looking at the columns of the matrix:

- , ,

This shows that:

- (1,0,0) has transformed to (0,0,1)

- (0,1,0) has transformed to (0,1,0) - it is invariant.

- (0,0,1) has transformed to (1,0,0)

In other words, (1,0,0) and (0,0,1) have swapped places, while (0,1,0) remains where it is.

In theory, these three points give enough information to define the whole transformation.

We can easily figure that an obvious swap must represent a reflection. With a bit of visualisation, we can see that it has to be a reflection across the plane .

Rotations

Rotations in 2D are of the form .

This gives a rotation anti-clockwise by angle with centre of rotation at the origin (which is invariant).

Note that the determinant, . So, the area of the shape will be multiplied by 1, and the orientation of the shape will not be flipped. A rotation is never the same as a reflection.

A 2D rotation matrix might look like: . Although a 2D rotation looks similar to a 2D reflection, the negative signs are in relatively different places.

3D Rotations

Rotation in 3D around the x-axis involves holding the x-coordinates constant. We'll see the first column of this rotation as , while the other two columns will look like a 2D rotation.

The matrix rotates anti-clockwise by angle , when looking from the point of view of the positive x-axis towards the origin.

Then you have:

- . Note that the negative sign in appears in the 'wrong' place, corresponding to the checkerboard pattern we often see when working with matrices. This maintains an anti-clockwise rotation when viewing from the positive y-axis towards the origin.

- .

Any rotation in 3D (about any line through the origin) can be expressed as a combination of these basic rotations.

So, if I want to rotate 30 degrees around the x-axis, and then 45 degrees around the y-axis, I will calculate the combined transformation matrix as follows:

The first transformation is on the right of the multiplication (imagine you are applying the matrix to at the end). Then, the second transformation will be "premultiplied" on the left. Rotations around different axes in 3D are not commutative - the order of the rotations, and therefore the order of the matrices, will matter!

Enlargements

Enlargements in 2D are of the form , a multiple of the identity matrix.

All points are enlarged, in every direction, by scale factor .

If , then the transformation will act to shrink everything towards the origin. We will often still call this an 'enlargement with scale factor k'.

As in all linear transformations, the origin will remain invariant.

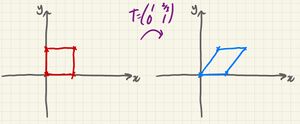

Stretches

Stretch parallel to the x-axis

Stretches parallel to the x-axis (in 2D) are of the form .

The point (a,b) will be stretched to the point (ka,b), as follows:

So, points on the y-axis (where ) will be invariant.

Stretch parallel to the y-axis

A stretch parallel to the y-axis will transform only the y-coordinate; the x-coordinate will remain unchanged.

Stretches parallel to the y-axis (in 2D) are of the form .

Where , the transformation will multiply the y-coordinate of each point by 1. This has no effect: notice that the matrix becomes the identity matrix, .

Where , the y-coordinate is reduced. We can think about this as a shrink or a squash, although we'll usually still call this an enlargement with scale factor .

Where , the whole xy-plane is squashed onto the x-axis. This is a singularity, with .

Where , the y-coordinate is negated. This represents a reflection across the x-axis together with a stretch. If , then it's just a pure reflection.

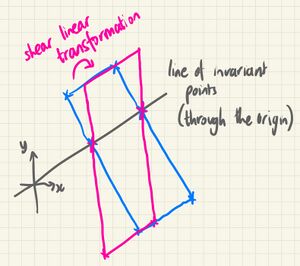

Shears

A shear keeps all the points on one line invariant, while other points 'slide' parallel to this line, according to how far away they are.

At A-Level, we only need to think about shears parallel to the two axes.

Shear Parallel to the x-Axis

A shear parallel to the x-axis will keep the x-axis invariant (the x-axis will be a line of invariant points). As such, the point with position vector , (1,0) on the x-axis, will shear to (1,0) (invariant).

The point with position vector , (0,1) is not on the x-axis, so it will shear across to (k,1).

Therefore, the matrix of a shear parallel to the x-axis will always be of the form: .

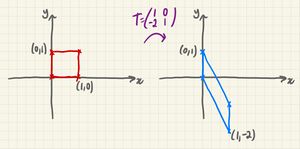

Shear Parallel to the y-Axis

A shear parallel to the y-axis will keep the y-axis invariant (the y-axis will be a line of invariant points). As such, the point (0,1) on the y-axis will remain invariant at (0,1).

The point (1,0) will shear parallel to the y-axis, up to (1,k).

Therefore, the matrix of a shear parallel to the x-axis will always be of the form: .

Shear Transformation: Area and Determinant

The shears above have transformed the unit square into a parallelogram with the same area - the image parallelogram will have same length of base, and same perpendicular height as the original square.

Since the area of any shape is unchanged, the matrix of a shear must have determinant 1.

Shear Defined by an Invariant Axis and a Point

A shear can be fully defined by its invariant line and the image of one other point.

Shear Defined by an Invariant Axis and a Point - Example

If we have a shear where the x-axis is invariant and (5,3) transforms to a point where x=17, this is enough to determine the whole transformation matrix.

First, note that (1,0) is on the x-axis and invariant. So the image of (1,0) must still be (1,0).

Second, note that (5,3) must shear parallel to the x-axis. So, the y-coordinate remains constant and this point transforms to (17,3).

So, we know and . We could now solve for M algebraically, by multiplying out the matrix.

Alternatively, we can consider that the 'shear factor'. A point 3 units away from the x-axis is sheared by 12 to the right - the 'shear factor' is . In other words, the point (0,1) will transform to (4,1).

We conclude that .

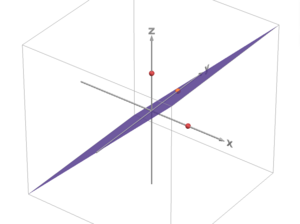

Singularities

Whenever , we call this a singular matrix. We can't find the inverse of this matrix.

In transformations, a 'singular' matrix is one that creates a 'singularity' - literally comparable to a black hole.

There is some reason we cannot reverse this transformation. Information about the original state has been lost.

Possibilities include:

- All of 3D-space has been transformed to a single plane,

- 3D-space has been transformed onto a single line,

- 2D-space has been transformed onto a single line,

- Everything has been reduced onto the origin (zero matrix).

In general, two points will have been transformed onto the same point, making the transformation irreversible.

Translations are not Linear

A translation is NOT a Linear Transformation! Since, for example, it moves the origin. That means that we can't represent a 2D translation with a 2x2 matrix - matrices are normally only capable of representing linear transformations.

However, we can apply a trick: we can use a 3x3 matrix to represent a translation in 2D. We'll call this type of translation an Affine Transformation - it has an affinity with linear transformations.